Businesses carry a lighter tax load in 2018

Running a profitable business these days isn’t easy. You have to operate efficiently, market aggressively and respond swiftly to competitive and financial challenges. But even when you do all of that, taxes may drag down your bottom line more than they should.

Running a profitable business these days isn’t easy. You have to operate efficiently, market aggressively and respond swiftly to competitive and financial challenges. But even when you do all of that, taxes may drag down your bottom line more than they should.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) will help reduce the 2018 tax burdens of many businesses and their owners. For C corporations and personal service corporations, it creates a low, flat tax rate and makes other changes. (See "What's new! The TCJA ushers in hefty tax cuts for corporations.") For sole proprietors and owners of pass-through entities, it provides relief as well. (See "What's new! The TCJA launches new deduction for pass-through businesses.") And for all entity types, it enhances many depreciation-related breaks. But the TCJA isn't all good news for businesses. (See "What's new! The TCJA reduces and eliminates some business tax breaks.")

If you own the business, it’s likely your biggest investment, so thinking about long-term considerations, such as your exit strategy, is critical as well. And if you’re an executive, you likely have to think about not only the company’s taxes, but also tax considerations related to compensation you receive beyond salary and bonuses, such as stock options. Planning for executive comp involves not only a variety of special rules but also several types of taxes — including ordinary income taxes, capital gains taxes, the NIIT and employment taxes. The TCJA also provides a bit of potential tax relief for certain types of executive comp. (See "What's new! The TCJA offers new, but limited, tax deferral opportunity.")

Depreciation

For assets with a useful life of more than one year, you generally must depreciate the cost over a period of years. In most cases the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) will be preferable to the straight-line method because you’ll get a larger deduction in the early years of an asset’s life.

But if you make more than 40% of the year’s asset purchases in the last quarter, you could be subject to the typically less favorable midquarter convention. When it comes to repairs and maintenance of tangible property, however, different rules may apply. Careful planning during the year can help you maximize depreciation deductions in the year of purchase.

Other depreciation-related breaks and strategies also are available, and in many cases enhanced by the TCJA:

Enhancement! Bonus depreciation.This additional first-year depreciation is available for qualified assets, which include new tangible property with a recovery period of 20 years or less (such as office furniture and equipment), off-the-shelf computer software, water utility property and, possibly, qualified improvement property.

Under the TCJA, for assets placed in service after Sept. 27, 2017, though Dec. 31, 2026, the definition has been expanded to include used property and qualified film, television and live theatrical productions. For qualified assets placed in service after Sept. 27, 2017, but before Jan. 1, 2023, bonus depreciation is 100% (up from 50%).

In later years, bonus depreciation is scheduled to be reduced as follows:

- 80% for 2023.

- 60% for 2024.

- 40% for 2025.

- 20% for 2026.

For certain property with longer production periods, these reductions are delayed by one year. For example, 80% bonus depreciation will apply to long-production-period property placed in service in 2024.

Warning: Under the TCJA, in some cases a business may not be eligible for bonus depreciation starting in 2018. Examples include real estate businesses that elect to deduct 100% of their business interest and dealerships with floor-plan financing, if they have average annual gross receipts of more than $25 million for the three previous tax years.

Enhancement! Section 179 expensing election. This allows you to deduct (rather than depreciate over a number of years) the cost of purchasing eligible new or used assets, such as equipment, furniture, off-the-shelf computer software, and qualified improvement property. Under the TCJA, for qualifying property placed in service in tax years beginning in 2018, the expensing limit increases to $1 million. The break begins to phase out dollar for dollar when asset acquisitions for the year exceed $2.5 million (compared to $2.03 million for 2017). For later tax years, these amounts will be indexed for inflation. You can claim the election only to offset net income, not to reduce it below zero to create a net operating loss.

Tangible property repair safe harbors. A business that has made repairs to tangible property, such as buildings, machinery, equipment and vehicles, can expense those costs and take an immediate deduction. But costs incurred to acquire, produce or improve tangible property must be depreciated. Distinguishing between repairs and improvements can be difficult. Fortunately, some IRS safe harbors can help: 1) the routine maintenance safe harbor, 2) the small business safe harbor, or 3) the de minimis safe harbor. The rules are complex, so contact your tax advisor for details.

Cost segregation study. If you’ve recently purchased or built a building or are remodeling existing space, consider a cost segregation study. It identifies property components and related costs that can be depreciated much faster and dramatically increase your current deductions. Typical assets that qualify include decorative fixtures, security equipment, parking lots, landscaping and architectural fees allocated to qualifying property. See the Case Study "Cost segregation study can accelerate depreciation."

The benefit of a cost segregation study may be limited in certain circumstances — for example, if the business is located in a state that doesn’t follow federal depreciation rules.

Vehicle-related tax breaks

Business-related vehicle expenses can be deducted using the mileage-rate method (54.5 cents per mile driven in 2018) or the actual-cost method (total out-of-pocket expenses for fuel, insurance and repairs, plus depreciation).

Purchases of new or used vehicles may be eligible for Sec. 179 expensing. However, many rules and limits apply. For example, the normal Sec. 179 expensing limit generally applies to vehicles with a gross vehicle weight rating of more than 14,000 pounds. A $25,000 limit applies to vehicles (typically SUVs) rated at more than 6,000 pounds but no more than 14,000 pounds.

Vehicles rated at 6,000 pounds or less don’t satisfy the SUV definition and thus are subject to the passenger vehicle limits. For passenger vehicles placed in service in 2018, the first-year depreciation limit is $18,000 ($10,000 plus $8,000 bonus depreciation). Warning: If bonus depreciation is elected, no additional depreciation can be taken until Year 7.

Also keep in mind that, if a vehicle is used for business and personal purposes, the associated expenses, including depreciation, must be allocated between deductible business use and nondeductible personal use. The depreciation limit is reduced if the business use is less than 100%. If business use is 50% or less, you can’t use Sec. 179 expensing or the accelerated regular MACRS; you must use the straightline method.

Employee benefits

Including a variety of benefits in your compensation package can help you not only attract and retain the best employees, but also manage your tax liability:

Qualified deferred compensation plans. These include pension, profit-sharing, SEP and 401(k) plans, as well as SIMPLEs. You can enjoy a tax deduction for your contributions to employees’ accounts, and the plans offer tax-deferred savings benefits for employees. Small employers (generally those with 100 or fewer employees) that create a retirement plan may be eligible for a $500 credit per year for three years. The credit is limited to 50% of qualified startup costs. (For more on the benefits to employees, see “401(k)s and other employer plans.”)

HSAs and FSAs. If you provide employees with a qualified high-deductible health plan (HDHP), you can also offer them Health Savings Accounts. Regardless of the type of health insurance you provide, you also can offer Flexible Spending Accounts for health care. If you have employees who incur day care expenses, consider offering FSAs for child and dependent care.

HRAs. A Health Reimbursement Account reimburses an employee for medical expenses up to a maximum dollar amount. Unlike an HSA, no HDHP is required. Unlike an FSA, any unused portion can be carried forward to the next year. But only the employer can contribute to an HRA.

Fringe benefits. Certain fringe benefits aren’t included in employee income, yet the employer can still deduct the portion, if any, that it pays and typically also avoid payroll taxes. Examples are employee discounts, group term-life insurance (up to $50,000 per person) and health insurance.

You might even be penalized for not offering health insurance. The play-or-pay provision of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) can in some cases impose a penalty on “large” employers if they don’t offer full-time employees “minimum essential coverage” or if the coverage offered is “unaffordable” or doesn’t provide “minimum value.”

The IRS has issued detailed guidance on what these terms mean and how employers can determine whether they’re a “large” employer and, if so, whether they’re offering sufficient coverage to avoid the risk of penalties.

NQDC. Nonqualified deferred compensation plans generally aren’t subject to nondiscrimination rules, so they can be used to provide substantial benefits to executives and other key employees. But the employer generally doesn’t get a deduction for NQDC plan contributions until the employee recognizes the income.

Tax credits

Tax credits can reduce tax liability dollar for dollar, making them particularly

beneficial. Some of the credits below had been proposed for repeal, but the final version of the TCJA that was signed into law retained them:

Research credit. The research credit (often called the “research and development” credit) gives businesses an incentive to step up their investments in research.

Certain start-ups (in general, those with less than $5 million in gross receipts) that haven’t yet incurred any income tax liability can use the credit against their payroll tax.

While the credit is complicated to compute, the tax savings can prove significant.

Work Opportunity credit. This credit is designed to encourage hiring from certain disadvantaged groups, such as certain veterans, ex-felons, individuals who’ve been unemployed for 27 weeks or more and food stamp recipients. Despite its proposed elimination, the credit survived and is available for 2018.

The size of the tax credit depends on the hired person’s target group, the wages paid to that person and the number of hours that person worked during the first year of employment. The maximum tax credit that can be earned for each member of a target group is generally $2,400 per adult employee. But the credit can be higher for members of certain target groups, up to as much as $9,600 for certain veterans.

Employers aren’t subject to a limit on the number of eligible individuals they can hire. That is, if there are 10 individuals that qualify, the credit can be 10 times the listed amount.

Bear in mind that you must obtain certification that an employee is a target group member from the appropriate State Workforce Agency before you can claim the credit. The certification generally must be requested within 28 days after the employee begins work.

New Markets credit. This credit gives investors who make “qualified equity investments” in certain low-income communities a 39% tax credit over a seven-year period. Certified Community Development Entities (CDEs) determine which projects get funded — often construction or rehabilitation real estate projects in “distressed” communities, using data from the 2006–2010 American Community Survey. Flexible financing is provided to the developers and business owners. The credit is scheduled to expire Dec. 31, 2019.

Retirement plan credit. Small employers (generally those with 100 or fewer employees) that create a retirement plan may be eligible for a $500 credit per year for three years. The credit is limited to 50% of qualified startup costs.

Small-business health care credit. The maximum credit is 50% of group health coverage premiums paid by the employer, provided it contributes at least 50% of the total premium or of a benchmark premium. For 2018, the full credit is available for employers with 10 or fewer full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) and average annual wages of less than $26,600 per employee. Partial credits are available on a sliding scale to businesses with fewer than 25 FTEs and average annual wages of less than $53,200. Warning: To qualify for the credit, online enrollment in the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) generally is required. In addition, the credit can be taken for only two years, and they must be consecutive. (Credits taken before 2014 don’t count, however.)

New! Family medical leave credit. For 2018 and 2019, the TCJA created a tax credit for qualifying employers that begin providing paid family and medical leave to their employees. The credit is equal to a minimum of 12.5% of the employee’s wages paid during that leave (up to 12 weeks per year) and can be as much as 25% of wages paid. Ordinary paid leave that employees are already entitled to doesn’t qualify. Additional rules and limits apply.

Exit planning

An exit strategy is a plan for passing on responsibility for running the company, transferring ownership and extracting your money from the business. This requires planning well in advance of the transition. Here are the most common exit options:

Buy-sell agreements. When a business has more than one owner, a buy-sell agreement can be a powerful tool. The agreement controls what happens to the business when a specified event occurs, such as an owner’s retirement, disability or death. Among other benefits, a well-drafted agreement:

- Provides a ready market for the departing owner’s shares,

- Sets a price for the shares, and

- Allows business continuity by preventing disagreements caused by

new owners.

A key issue with any buy-sell agreement is providing the buyer(s) with a means of funding the purchase. Life or disability insurance often helps fulfill this need and can give rise to several tax and nontax issues and opportunities.

One of the biggest advantages of life insurance as a funding method is that proceeds generally are excluded from the beneficiary’s taxable income. There are exceptions, however, so be sure to consult your tax advisor.

Succession within the family. You can pass your business on to family members by giving them interests, selling them interests or doing some of each. Be sure to consider your income needs, how family members will feel about your choice, and the gift and estate tax consequences. With the higher gift tax exemption in effect under the TCJA for the next several years, now may be a particularly good time to transfer ownership interests in your business. Valuation discounts may further reduce the taxable value of the gift.

Management buyout. If family members aren’t interested in or capable of taking over your business, one option is a management buyout. This may provide for a smooth transition because there may be little learning curve for the new owners. Plus you avoid the time and expense of finding an outside buyer.

ESOP. If you want rank and file employees to become owners as well, an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) may be the ticket. An ESOP is a qualified retirement plan created primarily to purchase your company’s stock. Whether you’re planning for liquidity, looking for a tax-favored loan or wanting to supplement an employee benefit program, an ESOP can offer many advantages.

Selling to an outsider. If you can find the right buyer, you may be able to sell the business at a premium. Putting your business into a sale-ready state can help you get the best price. This generally means transparent operations, assets in good working condition and minimal reliance on key people.

Sale or acquisition

Whether you’re selling your business as part of your exit strategy or acquiring another company to help grow it, the tax consequences can have a major impact on the transaction’s success or failure. Here are a few key tax considerations:

Asset vs. stock sale. With a corporation, sellers typically prefer a stock sale for the capital gains treatment and to avoid double taxation. Buyers generally want an asset sale to maximize future depreciation write-offs.

Taxable sale vs. tax-deferred transfer. A transfer of ownership of a corporation can be tax-deferred if made solely in exchange for stock or securities of the recipient corporation in a qualifying reorganization. But the transaction must comply with strict rules. Although it’s generally better to postpone tax, there are some advantages to a taxable sale:

- The seller doesn’t have to worry about the quality of buyer stock or other business

risks that might come with a tax-deferred transfer. - The buyer benefits by receiving a stepped-up basis in its acquisition’s assets.

- The parties don’t have to meet the technical requirements of a tax-deferred transfer.

Installment sale. A taxable sale might be structured as an installment sale if the buyer lacks sufficient cash or pays a contingent amount based on the business’s performance. An installment sale also may make sense if the seller wishes to spread the gain over a number of years — which could be especially beneficial if it would allow the seller to stay under the thresholds for triggering the 3.8% NIIT or the 20% long-term capital gains rate.

But an installment sale can backfire on the seller. For example, depreciation recapture must be reported as gain in the year of sale, no matter how much cash the seller receives. And, if tax rates increase, the overall tax could wind up being more. Of course, tax consequences are only one of many important considerations when planning a merger or acquisition.

Incentive stock options

If you’re an executive or other key employee with a larger company, you may receive incentive stock options (ISOs). ISOs receive tax-favored treatment but must comply with many rules. ISOs allow you to buy company stock in the future (but before a set expiration date) at a fixed price equal to or greater than the stock’s fair market value (FMV) at the date of the grant.

Therefore, ISOs don’t provide a benefit until the stock appreciates in value. If it does, you can buy shares at a price below what they’re then trading for, provided you’re eligible to exercise

the options. Here are the key tax consequences:

- You owe no tax when the ISOs are granted.

- You owe no regular tax when you exercise the ISOs.

- If you sell the stock after holding the shares at least one year from the date of exercise and two years from the date the ISOs were granted, you pay tax on the sale at your long-term capital gains rate.

- If you sell the stock before long-term capital gains treatment applies, a “disqualifying disposition” occurs and any gain is taxed as compensation at ordinary-income rates.

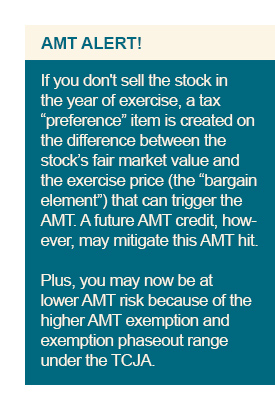

If you’ve received ISOs, plan carefully when to exercise them and whether to immediately sell shares received from an exercise or hold them. Waiting to exercise ISOs until just before the expiration date (when the stock value may be the highest, assuming the stock is appreciating) and holding on to the stock long enough to garner long-term capital gains treatment often is beneficial. But there’s also market risk to consider.

If you’ve received ISOs, plan carefully when to exercise them and whether to immediately sell shares received from an exercise or hold them. Waiting to exercise ISOs until just before the expiration date (when the stock value may be the highest, assuming the stock is appreciating) and holding on to the stock long enough to garner long-term capital gains treatment often is beneficial. But there’s also market risk to consider.

Plus, in several situations, acting earlier can be advantageous:

- Exercise early to start your holding period so you can sell and receive long-term capital gains treatment sooner.

- Exercise when the bargain element is small or when the market price is close to bottoming out to reduce or eliminate AMT liability.

- Exercise annually so you can buy only the number of shares that will achieve a breakeven point between the AMT and regular tax and thereby incur no additional tax.

- Sell in a disqualifying disposition and pay the higher ordinary-income rate to avoid the AMT on potentially disappearing appreciation.

On the negative side, exercising early accelerates the need for funds to buy the stock, exposes you to a loss if the shares’ value drops below your exercise cost, and may create a tax cost if the preference item from the exercise generates an AMT liability.

The timing of ISO exercises could also positively or negatively affect your liability for the higher ordinary-income tax rates, the 20% long-term capital gains rate or the NIIT. With your tax advisor, evaluate the risks and crunch the numbers using various assumptions to determine the best strategy for you.

Nonqualified stock options

The tax treatment of nonqualified stock options (NQSOs) is different from that of ISOs: NQSOs create compensation income (taxed at ordinary-income rates) on the bargain element when exercised (regardless of whether the stock is held or sold immediately), but they don’t create an AMT preference item.

You may need to make estimated tax payments or increase withholding to fully cover the tax on the exercise. Keep in mind that an exercise could trigger or increase exposure to top tax rates, the additional 0.9% Medicare tax and the NIIT.

Restricted stock

Restricted stock is stock your employer grants to you substantial risk of forfeiture. Income recognition is normally deferred until the stock is no longer subject to that risk (that is, it’s vested) or you sell it. You then pay taxes based on the stock’s fair market value when the restriction lapses and at your ordinary-income rate. (The FMV will be considered FICA income, so it could trigger or increase your exposure to the additional 0.9% Medicare tax.)

But, under Section 83(b), you can elect to instead recognize ordinary income when you receive the stock. This election, which you must make within 30 days after receiving the stock, allows you to convert future appreciation from ordinary income to long-term capital gains income and defer it until the stock is sold.

The election can be beneficial if the income at the grant date is negligible or the stock is likely to appreciate significantly before income would otherwise be recognized. And with ordinary-income rates now especially low under the TCJA, it might be a good time to recognize income.

There are some disadvantages of a Sec. 83(b) election: First, you must prepay tax in the current year — which also could push you into a higher income tax bracket and trigger or increase your exposure to the additional 0.9% Medicare tax. But if a company is in the earlier stages of development, the income recognized may be small. Second, any taxes you pay because of the election can’t be refunded if you eventually forfeit the stock or you sell it at a decreased value. But you’d have a capital loss when you forfeited or sold the stock. Third, when you sell the shares, any gain will be included in net investment income and could trigger or increase your liability for the 3.8% NIIT.

Work with your tax advisor to map out whether the Sec. 83(b) election is appropriate for you in each particular situation.

RSUs

RSUs are contractual rights to receive stock (or its cash value) after the award has vested. Unlike restricted stock, RSUs aren’t eligible for the Sec. 83(b) election. So there’s no opportunity to convert ordinary income into capital gains.

But they do offer a limited ability to defer income taxes: Unlike restricted stock, which becomes taxable immediately upon vesting, RSUs aren’t taxable until the employee actually receives the stock. So rather than having the stock delivered immediately upon vesting, you may be able to arrange with your employer to delay delivery. This will defer income tax and may allow you to reduce or avoid exposure to the additional 0.9% Medicare tax (because the RSUs are treated as FICA income).

However, any income deferral must satisfy the strict requirements of Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 409A. Also keep in mind that it might be better to recognize income now because of the currently low tax rates.

NQDC plans

Nonqualified deferred compensation plans pay executives in the future for services to be currently performed. They differ from qualified plans, such as 401(k)s, in several ways. For example, unlike 401(k) plans, NQDC plans can favor highly compensated employees, but any NQDC plan funding isn’t protected from the employer’s creditors.

Some major changes to the taxation of NQDC that had been included in original versions of the TCJA would have negatively impacted such compensation. Fortunately, those changes didn’t make it into the final version that was signed into law.

One important NQDC tax issue is that employment taxes are generally due once services have been performed and there’s no longer a substantial risk of forfeiture — even though compensation may not be paid or recognized for income tax purposes until much later. So your employer may withhold your portion of the payroll taxes from your salary or ask you to write a check for the liability. Or it may pay your portion, in which case you’ll have additional taxable income. Warning: The additional 0.9% Medicare tax could also apply.

Keep in mind that the rules for NQDC plans are tighter than they once were, and the penalties for noncompliance can be severe: You could be taxed on plan benefits at the time of vesting, and a 20% penalty and potential interest charges also could apply. So check with your employer to make sure it’s addressing any compliance issues.